Apocalypse World introduced the word “clocks” to storygaming. Ye olde AW clocks were checklists of escalating narrative events. The MC could tick a slice of that clock and the event associated with that tick would happen. Or if the listed event happened, the MC could advance the clock to that point. AW clocks are prescriptive and descriptive, and always the same length. When the clock is complete, some big change in the fiction happens.

Clocks as they’re understood in Forged in the Dark games are a different critter, despite sharing a name with AW’s version. If you haven’t read or played these games, FitD style clocks in short: set up a little circle with (traditionally) an even number of slices, 4 to 10. Filling a clock means a fictional event comes to pass: you kill the big monster, you convince the village elder to provision your troops, you get into your arch-enemy’s inner sanctum. The individual slices, though, are fungible. After chatting with folks on our Slack, it seems there’s a combination of PbtA baggage and insufficient explanation in the rulebooks about how to best use Blades in the Dark-style clocks.

I believe clocks are one of FitD’s two killer apps (this other is position/effect, which I talked about a little but I’ll dig into more at some point). In my opinion, clocks are so central to the game that you cannot treat them as optional.

I’ve been experimenting with clocks for a while now. Here are some ideas.

Wherein I Completely Screw Up These Newfangled Clocks

My first exposure to these new clocks was via an early release candidate of Blades in the Dark. Can’t remember which one, maybe rc7 or so? Anyway! The only other place I’d seen the word “clock” was Apocalypse World. In AW, a clock tracks progress in your Fronts; they’re a campaign pacing tool.

In BitD, though, you can use “clocks” to track progress for events within a job or even across the campaign. That early PDF had a good but brief explanation. I couldn’t really see how clocks fit into the game, though, and assumed they were optional.

The big revelation came when our starting gang attempted what should have been a milk run, and everyone ended up dead or nearly dead. Every time they rolled anything less than a 6, I’d load ‘em up with consequences. I had no place to put consequences other than the characters or the fiction, and the whole thing ended up looking more like a game of Fiasco than smooth Ocean’s 11 style criming. The reason of course is that you need clocks as a place to put consequences other than the characters and the fiction.

The next FitD we played, Scum and Villainy, is structurally very similar to Blades, so I had a better grasp of why I might want to deploy more clocks, but not necessarily how I might do that. Again I went to the rulebook. Lots of formats – racing clocks, countdown clocks, and so on – but not much talk about best practices. I experimented with running more clocks every session.

Band of Blades, the most recent FitD from Off Guard Games, is where I think I’ve finally nailed down a solid set of practices to really make clocks sing.

The Secret of Clocks

Here is what I think about when I say clocks are a killer app:

- You can bleed off consequences into them

- Starting and ticking clocks make good Devil’s Bargains

- It’s a way to (sneakily!) collaborate with the players to introduce campaign-scale changes

- They’re a fun toolkit for GMs who love designing minigames on the spot

- They provide a focal point on the table for players to focus on. (Long-standing IGRC theory: every RPG needs something on the table to look at.)

I want to talk about each of these.

Consequence Sinks

The big, practical point I first learned about FitD clocks is that the GM needs someplace to put consequences other than directly on the characters, or an immediate complication in the fiction. To my taste, going straight to harm makes the characters seem too fragile, and going straight to complications makes the mission too zany.

I’m careful not to play into my win-driven players’ urges to amortize resources across clock ticks or anything like that. When I put that first clock out, it’s usually a big twist that is looming over the whole mission. Two slices per player seems like a pretty good size; it gives each of them one risky-sized consequence and/or one normal-sized success. Resisting those clock ticks in the future seems reasonable. Luring players into stressing out by over-resisting is always a good idea. It’s also big enough that, if it’s a clock they need to complete to accomplish something in the mission, they’re tempted to trade position for effect, or to push for effect, so they can run the clock faster.

I might go a little bigger if it seems “hard” or if it’s interesting to me, or smaller if it seems like it’s bigger than a single task but I’m not that into digging into it. It’s definitely a place where you need to experiment.

This doesn’t mean not applying harm or using up gear or complicating the fiction. It means the GM can do, like, one of those things and also tick a clock. Big fictional moves also feel more satisfying to me than whittling away at characters’ competence.

Devil’s Bargains and Democratized Fiction

When the player asks for a Devil’s Bargain, one of my favorite tricks is to offer them a new, empty clock. It feels like a freebie, doesn’t it? Here’s a new clock, just take it, no worries. But here’s the trick: the existence of that clock is an alibi for the GM to play toward that new possibility. Maybe it was always possible that your gang would attract the attention of a much bigger, scarier organization, sure. But now that it’s a clock, it’s much more pressing. A clock is announcing future badness, and it’s badness the player agreed to.

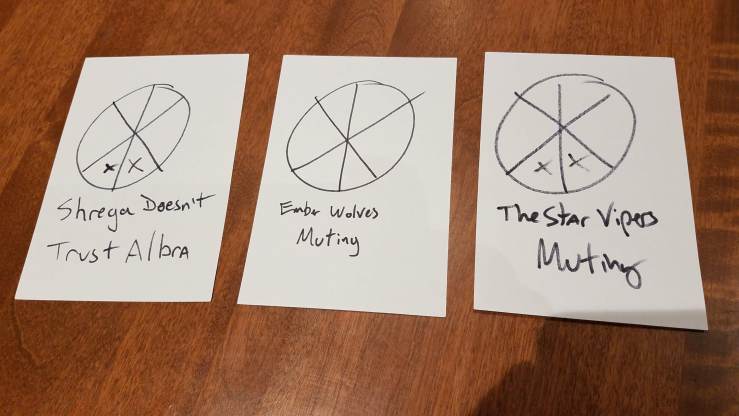

The point here is that offering new clocks as Devil’s Bargains means I’m asking the player, “What do you think about adding this new idea?” And that idea might just be the size of the mission, or it might be a campaign-long threat. I love big-picture clocks that endure beyond the mission that introduced them. It’s like creating a new, small Front right on the spot. In our Band of Blades game, we have clocks ticking down for a couple squads that might desert, as well as their Chosen deciding she doesn’t trust the Legion’s officer.

The theatrics of putting the clock on the table are important! I don’t like having more than three or four campaign-scale clocks running at once, though. The chances of any clock happening drops with each new clock. That’s a feel thing. But those clocks? They’re something for everyone to look at and think about. It keeps those fictional elements at front-of-mind.

Minigame Toolkit

This might just be me but I’m betting it isn’t: I love, love designing little minigames within a session. Deploying and ticking clocks in various ways is just darned fun when I GM.

The books lay out various kinds of clocks, and I direct you to those texts for details. But here are some fun games I’ve worked out.

The Kick the Can clock: this is where I put out a clock that looks like a freebie of a Devil’s Bargain. Want the die? Great, here’s my proposal for a clock. Future DBs might just be more ticks. Those also feel like freebies! This is a gift because, honestly, every roll in the game involves offering a devil’s bargain and a set of consequences, and that adds up to be a pretty big creative lift. Eventually, usually around half the clock filled, the players start thinking twice about taking those free ticks. That’s good tension. Can you press your luck before the clock runs out?

The Bait and Switch clock: This is when that Kick the Can clock is more than half over, and I start dropping ticks on it as consequences. Now it’s not a free die bank, it’s a sink for their consequences. It makes the looming threat feel like it’s accelerating, which is delicious.

The Rigged Race clock: Racing clocks are nice and all – and they’re necessary when there’s the possibility of actual failure – but you know what’s really fun? Making the “you lose” side of the game shorter than the “you win” side. So unfair! I use a light touch on this, though. My personal practice is to offer the clock but not reveal how many ticks I had in mind. My players are usually – but not always! – okay with me revealing that the race is rigged.

The Recontextualized clock: This is where the players were working on filling a clock up to accomplish something, but timing was vital and the GM completes the clock as a consequence before they were ready. This has everything to do with fictional positioning, since the players get what the clock says they got, right? But getting what they wanted before they’re ready for it, that’s the trick.

In our latest Band of Blades game, the Legion arrived in a village looking to exfiltrate a valuable Orite scholar who had snuck out a message claiming she was being held by the Broken. They arrive and quickly discover the townsfolk are being terrorized: their houses were filled with zombified villagers waiting for a signal from the Big Bad lurking in a big barn. They were cattle awaiting slaughter. The Legion sets up an 8-segment clock: “defeat the zombie villagers” and start working through it.

First they rigged up explosives that are set to go off when the zombies come running out of the houses. Next, they secretly communicate with village leaders that they should run like hell out of the houses when the squad fires a flare gun. That put them at 6 of their 8 ticks. Then a different clock went off, “the thing in the barn takes notice,” and they find themselves in a pitched battle with this huge horror! The first consequence in their battle against the Horror is 3 ticks on their “defeat the zombie villagers” clock, as the zombies run out to join their master…triggering the bombs. With the villagers still inside their houses. Oh woe! You monsters!

That’s what I mean by recontextualized: the thing they were working toward plays out, but not how they intended.

Setting Up Good Clocks

One place I’ve heard confusion, including my own confusion early on, is figuring out just how much you can accomplish with a clock.

I think the common mistake is to get too specific with what will happen when the clock is complete. The players might want to scale the walls of a fortress, but making a “get over the wall” clock can get weird and boring: You maneuver, you maneuver, oh darn you’ve got 2 ticks left, you maneuver again I guess…Yawn.

When I set up a clock, I pull the camera back far enough that a) I can see various actions taking place to accomplish it and b) the thing they accomplish is broadly defined. So like “get into the fortress” would be a better clock in the above example because you could start by climbing the wall…and then sneaking past the guards…and then bypassing the locks on the door. Or whatever. But “get into” is so loose that nobody feels trapped to repeat actions.

The clock also needs to provide measurable changes in the fiction. Like moves in PbtA, the fiction should be meaningfully moved by the clock should it come to pass.

Setting up clock sizes is … hard. I mostly default to 8 ticks in Band, that is, 2 ticks per player at my table. It’s not always the right answer. When they’re dealing with a squad of bad guys in Band of Blades, I’ll more or less map ticks to the number of critters in the squad as well: 6 ticks is 6 zombies, or whatever, and I’ll adjust their Scale down as the ticks eat through the monsters.

One thing that can happen is that everyone’s done what feels like a reasonable action toward filling a clock and it still isn’t filled. I recall how InSpectres, which uses a similar “you’re done!” metric, can feel when the fiction is exhausted but the score isn’t high enough yet. I think this is a matter of, as GM, looking ahead at how many ticks will be left, and providing complications that clearly illustrate why they’re not done when they thought they would be. This isn’t rocket science and most folks probably are doing this, just a friendly reminder. If it’s happening anyway, odds are good the move was designed to accomplish a task and not reposition the fiction.

In Conclusion

- FitD clocks are fundamentally different tech than PbtA clocks. Don’t confuse them!

- Clocks should result in a meaningful shift in the fiction, not just a discrete task.

- They’re just darned fun to play with if you have a head for design.

- They’re super helpful to the GM on both the Devil’s Bargain end and the consequence end of each transaction

I think another really important things about clocks that clicked with me between the session I ran tonight and reading your post here is how effective they are at adjudicating effect. Is in position/effect.

Like at one point in my game last night the Scout was trying to lay low and wait for a patrol to pass. Because of the situation it was a desperate action and I decided it would be limited effect. And the immediate question was “what does limited effect in this instance mean?”. I didn’t have a good answer. We sort of stumbled through the scene and it was fine, but I spent the rest of the night trying to decide what limited effect would mean in that instance.

When harm is involved, that’s pretty easy.

Finally I started thinking, maybe the whole escape should have been a clock. The specialist on the mission and the 2 PC rookies all had their moment to get past the patrols. I realized that most of the same fiction could have been generated, but if there’d been a clock on the table it could have solidified things a lot more.

This is a note to myself to really think more about using clocks and what they can represent. Especially after last night when a lot of the action involved moving into position or sneaking about. It gets old and samey. The situation could have been a lot more dynamic with a couple clocks involved.

And I love the idea of a devil’s bargain to add a new clock with no ticks. That’s brilliant and I never would have thought about it. When I’ve offered clocks as devil’s bargains before I always start them with a tick or two.

Still going! This is part 6 of 9. I’ll post another every few days so you have time to catch up. If you’ve just run…